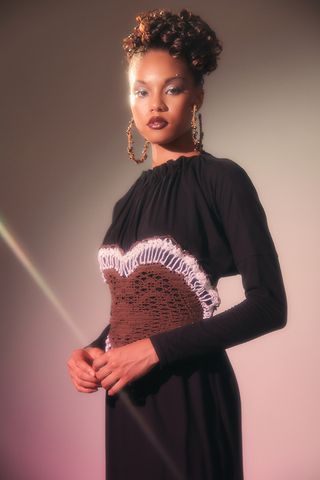

The Brooklyn designer weaving her Caribbean roots into crochet

Layered and multifaceted, designer and founder of Diotima, Rachel Scott imbues her collection with her Carribean heritage, dance hall culture and fine Italian fabrics

Designer Rachel Scott’s approach to fashion is both personal and theoretical, historical and forward-looking. Born in Kingston, Jamaica, Scott now lives in Brooklyn, New York, with her photographer husband. ‘I have been working in the fashion industry for 15 years, but this has always been a goal,' she says of Diotima, the line she launched from the studio that she set up in her home during the pandemic.

Scott left Jamaica 20 years ago to study art and French philosophy at Colgate University in New York. The label takes its name from the ancient Greek priestess and philosopher Diotima of Mantinea. ‘The past few years I’ve continued studying philosophy recreationally,' says Scott breezily. ‘Diotima is fascinating because it’s never been clear if she was real or mythical,' she says, referencing Plato’s Ladder of Love. ‘When I’m designing, I try to approach it with the idea of working trans-historically – with history and the future.' Landing a place at Istituto Marangoni in Milan, she swerved to study fashion design, gaining a job at Costume National which she describes as ‘a wonderful experience, an excellent education.' She learnt the rigour of a major Italian fashion house. ‘There was such a reverence for craft,' she recalls. Today, she is vice president of design for Rachel Comey, where she has worked since 2015.

The pandemic allowed for a moment of reflection on how the fashion world was operating. ‘Major orders were being cancelled and it impacted the factories and their people. Somehow the liability always ends up on the most vulnerable person, pushing the issues from the stores onto the designers, to the manufacturers, to the person doing the labor at the end of the chain. I wanted to change my relationship to labour.'

Diotima: ‘You can always spot Carribeans anywhere because we are so proud of it.'

During the pandemic she made two trips home to the Blue Mountains in Jamaica, and while there, sought out the expertise of two local crochet makers. ‘When the borders closed during the pandemic, they lost all their tourism trade. I thought, ‘What can I do?’ So I started talking to them over WhatsApp from New York about making some crochet pieces. The rest of Diotima's collection was made from very limited deadstock fabric in the US.' Now she works with 12 women in Kingston, including some younger women who are learning the trade. What is not made in Jamaica, Scott produces in New York. ‘I take a lot of inspiration from New York. Not just manufacturing in the garment district, which is very much alive, but also so much about relationships and collaborations, making new connections,' she says.

Scott’s roots are inextricably woven into her designs. Powerful and seductive, dancehall culture is ingrained in her clothes. ‘The explosive dance and music means so much possibility for liberation,' she says. ‘Carlene Smith was super influential to me as a teenager,' she says of the Jamaican dance hall icon. ‘And the female musicians of this Caribbean postcolonial nation. It was such a fascinating time of gender dynamics. Carlene was not trying to operate in a man’s world as a man, but owning it as herself.'

There are some literal dancehall references in the collection, such as the lacebody suits, short ‘batty rider’ shorts, masculine Nineties-style oversized boxy jackets and shirts. A macrame t-shirt finished with Swarovski crystals, a marina string vest lined with bias cut silk, and a pleated skirt inspired by her prim Jesuit school uniform are elevated versions of the original incarnations. Biographical scenes of domesticity crop up – she’s ‘obsessed with chintzes'; there’s a starched doily top; and a skirt that borrows from a table runner and is unexpectedly slit high on the thigh.

Scott explored the Caribbean tradition of Junkanoo carnival for her Pre-Spring ‘22 collection. ‘Historically, this would take place on Boxing Day, when slaves would be given the day off by their owners and the men would dress up as women, playing characters such as the plantation owner’s wife. I started deconstructing this moment, and playing with tropes of what a woman should be,' she says. ‘Reggae, ska and dancehall music was influenced by these early carnivals.'

The designer pays great attention to her fabrics. Diotima's luxurious Italian tweed suiting is treated with a pigment print to create an interesting texture. A neutral and earthy palette is punctuated with red, white and pink colours from the Junkanoo carnival.

‘The BLM movement in the US has been so important in highlighting which voices get heard and which don’t. As a woman of colour, I used to feel that if there was someone working as a Black or Carribean designer, that there was no more room for another voice. But now I know that’s not the case,' she says. ‘I always knew I wanted to try and find a way to not contribute to the Caribbean's brain drain – the youth and energy that leaves to find work elsewhere,' she says of the industry she is building in Jamaica. ‘You can always spot Carribeans anywhere because we are so proud of it.'

INFORMATION

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tilly is a British writer, editor and digital consultant based in New York, covering luxury fashion, jewellery, design, culture, art, travel, wellness and more. An alumna of Central Saint Martins, she is Contributing Editor for Wallpaper* and has interviewed a cross section of design legends including Sir David Adjaye, Samuel Ross, Pamela Shamshiri and Piet Oudolf for the magazine.

-

Shigeru Ban wins 2024 Praemium Imperiale Architecture Award

Shigeru Ban wins 2024 Praemium Imperiale Architecture AwardThe 2024 Praemium Imperiale Architecture Award goes to Japanese architect Shigeru Ban

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Stone Island and New Balance team up for this year’s most sought-after sneaker

Stone Island and New Balance team up for this year’s most sought-after sneakerPart of Stone Island’s monochromatic ‘Ghost’ line, the collaboration is inspired by both brand’s longtime links with British subculture

By Jack Moss Published

-

Step inside Apple Park Observatory, the tech giant's new hub for events and innovation in Cupertino

Step inside Apple Park Observatory, the tech giant's new hub for events and innovation in CupertinoApple Park Observatory, unveiled in Cupertino, adds to the tech giant's expansive campus by Foster + Partners in California

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

In Kyoto, COS celebrates the ancient art of shibori dyeing with a colour-soaked collection

In Kyoto, COS celebrates the ancient art of shibori dyeing with a colour-soaked collection‘We can’t take this type of craft for granted anymore,’ says COS design director Karin Gustafsson, who worked with Kyoto shibori artisan Kazuki Tabata on the airy summer collection. Wallpaper* heads to Japan’s former capital to find out more

By Jack Moss Published

-

Handwoven basket bags by Uri celebrate Filipino craft

Handwoven basket bags by Uri celebrate Filipino craftBy Pei-Ru Keh Last updated

-

Remote Japanese concept store celebrates the future of craft

Remote Japanese concept store celebrates the future of craftLes Six, a new concept store in South Japan, sells crafted wares for a new world

By Minako Norimatsu Last updated

-

Loewe basket weave tops are wearable sculptures

Loewe basket weave tops are wearable sculpturesThe Spanish brand's S/S 2021 men's collection features two leather tops, basket-woven by Galicia-based textile artist Idoia Cuesta

By Laura Hawkins Last updated

-

Loewe Weaves collection launches with Sotheby's

Loewe Weaves collection launches with Sotheby'sSpanish luxury house Loewe launches a series of artist-designed chestnut roasters, in collaboration with Sotheby's Buy Now platform

By Laura Hawkins Last updated

-

Blue sky thinking: Loewe celebrates Ken Price's optimistic ceramics

Blue sky thinking: Loewe celebrates Ken Price's optimistic ceramicsA capsule collection by the Madrid-based label features illustrative artworks by the American artist

By Laura Hawkins Last updated