‘Modern beauty’: Pieter Mulier on his new vision for Alaïa

As creative director of Alaïa, Belgian designer Pieter Mulier honours the timeless vision of the maison’s founder while rewriting the past anew. Here, speaking to Jack Moss, he tells the story behind his first year at the house

Until Pieter Mulier was named creative director of Alaïa in February 2021, he was largely known only by fashion insiders; he was a right-hand man, the confidante and creative partner of fellow Belgian Raf Simons, whom he first worked for as an intern at the latter’s eponymous label in the early 2000s. Their partnership would continue during Simons’ tenures at Jil Sander, Dior, and finally Calvin Klein, where, in 2016, Mulier was made global creative director to Simons’ chief creative officer (there, after the presentation of each collection, they would take their bow as a pair). Two years later, they exited the American behemoth together. Mulier cited ‘fashion burnout’. ‘At some point, I started asking myself: who buys all this?’ he said at a talk last year in Antwerp.

In 2014, Frédéric Tcheng’s documentary Dior & I (see W*192) provided a glimpse into this rare and enduring creative partnership, capturing the eight-week period Simons was given to create his debut couture collection for the historic French house. Simons is mercurial, at times conflicted; Mulier is diligent, well-mannered, smoothing the link between Simons and the atelier (Mulier speaks French, Simons only a little). In one scene, each member of the atelier is asked to select a look from the collection to create – a recognition of the emotional resonance of couture, whereby each garment is forever linked to the singular hand that made it, and the singular body that it was made for.

After the show, Simons takes his runway bow in tears; Mulier, watching backstage, is equally moved. ‘I’m only doing couture now,’ he whispers with a smile to one of the atelier team.

Dress, £5,030; shoes, £1760, both by Alaïa

Seven years on, in July 2021, Mulier was ready to take his own place in the spotlight, presenting his first collection for Alaïa during haute couture week in Paris. Simons was there too, but this time he sat front row in support (no less emotional, Simons was again in tears during the show’s finale). It was a special moment for Mulier, but also for the house – presented in a brief respite from pandemic restrictions, it marked the first show since the death of Azzedine Alaïa in 2017. The show was held outside, on Rue de Moussy, the narrow Marais street that runs alongside the Alaïa headquarters, a jumble of adjoining buildings around a courtyard housing a sculpture of a woman’s breast (by César Baldaccini, a longtime friend and collaborator of Alaïa). There’s a store, a three-room hotel, a vaulted showspace, and what had been the Tunisian designer’s personal residence in his lifetime. Such is the late Alaïa’s imprint, Mulier calls it ‘the cathedral’.

The show itself began with a letter – left on attendees’ chairs in lieu of traditional collection notes – providing a heartfelt address from Mulier to ‘dear Azzedine’, which paid tribute to the couturier, a ‘thank you... to express [to] you my sincere respect, and recognition for the work you did’, he wrote. ‘Four years after your final presentation, today, on the fourth of July, I feel honoured to be presenting this collection. I tried to be faithful to your creative approach. I even tried to get into your mind... but that’s impossible. I have so many questions. So many things I imagine. You. Passionate, stubborn, charming.’

It was a moment of reverence for one of fashion’s great iconoclasts, who rejected the industry’s churning desire for newness with collections that focused not on ephemeral trends but a dogged pursuit of beauty, often presented off-schedule and always on his own terms. Born in Tunis, Tunisia, in 1935, the young Alaïa attended Tunis’ School of Fine Arts before later travelling to Paris to take up a job at Christian Dior in 1957. In 1979, he started his eponymous label, having built up a network of high-profile clients across the city. He showed his first collection in 1980.

Top, dress, price on request, by Alaïa. Above, bodysuit, £1,140; trousers, £2740; metal cuff, £700; pale yellow cuff, £490; boots, £1,760, all by Alaïa

Alaïa approached design with a sculptor’s hand, using cloth as his medium; the resulting collections were defSpela Kasal ined as much by technical feats of construction – years-in-development stretch fabrics, moulded and laser-cut leather, internal corsetry, elements reminiscent of industrial design – as his innate understanding of sensuality and glamour (he is variously deemed ‘the king of cling’ and ‘the last couturier’). A 2015 exhibition of his work at Rome’s Villa Borghese placed his gowns alongside the marble statues of Bernini and Canova, but Alaïa was most delighted to see his clothing on women’s bodies, particularly those whom he loved – moving, breathing, living.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Alaïa was particularly fond of company; famously, he would host dinners around his kitchen table at Rue de Moussy, his beloved dogs alongside, for members of the atelier, friends, and luminaries of the worlds of fashion, art and music (often he would leave after the meal had finished and head back to the studio to work until the morning). ‘He used to gather people of all walks of life around him,’ says Mulier, speaking from his home in Antwerp, where he retreats each weekend to escape Paris. ‘He used to put women at the heart of creation, endlessly seeking the essence of femininity, with a benevolent eye and respect. That’s what I want to keep and protect: Alaïa’s family spirit, which makes the house so special.’

‘I want to create clothes that carry this idea of a modern beauty, always in movement’

Pieter Mulier

Mulier previously noted the ‘human scale’ of Alaïa as one of the reasons he was lured to the job, despite purportedly being offered roles at larger houses. He references Alaïa as a ‘small ship’, a tightly-knit team, many of whom worked under Alaïa himself, carrying with them unique – and often surprising – knowledge of construction, fabric and form. ‘I like the idea of working with a small but devoted team of highly skilled technicians and dressmakers. It’s a reminder of the purest form of fashion,’ he says. ‘It’s a big problem if you make clothes without knowing the people who will help you to build them. And also without knowing who is wearing them. The women who wear Alaïa are not static works of art, but are active in society, working, running, busy with children. I want to create clothes that carry this idea of a modern beauty, always in movement.’

Catsuit, £2,120; shoes, £1,190, both by Alaïa

When Mulier arrived at the maison, he called himself a ‘caretaker’; now, just over a year on from his appointment, he says he feels a stronger desire to ‘evolve’ Alaïa, to create a ‘modern’ Parisian house, without ever straying too far from its foundations. ‘I think Alaïa isn’t huge, and that is what makes it so special. You don’t have to make a compromise in terms of creation.’ He says he wants to make Alaïa more ‘democratic’, to open its doors to the world. ‘That’s how I want to build the future of this legendary house; I can’t change everything – and I don’t want to. But I want to try and give Alaïa to a bigger audience, to make it more inclusive.’

Mulier remains an avid student of the Alaïa archive, having spent ‘countless days and nights’ teaching himself the intricacies of the house’s unique design language in order to reinterpret them for the present day (he notes a particular focus on the years 1983-1996, ‘when the clothes invented by Azzedine were revolutionary works of art’). Richemont, the Swiss luxury goods conglomerate that owns Alaïa, gave Mulier the rare gift of time in the run-up to his announcement as creative director; for several months prior, he had been quietly honing his vision in a series of presentations to executives at Richemont and the house. During those months, he ordered various archival pieces from the internet, fascinated by the construction of each garment, much of which is hidden from view when worn. He notes that such details appeal to his architectural sensibilities – Mulier studied not fashion but architecture, at Institut Saint-Luc in Brussels. He was also struck by the enduring modernity of each piece. ‘They can still be worn today – that’s what I want to continue to create, clothes that will stand the test of time.’

If Mulier’s debut collection was one of reverence, his sophomore outing (dubbed Summer Fall 22 and presented this past January) sees the designer crystallise his own vision of the house – no full-scale revolution, to be sure, but an allowance to pursue his own conception of beauty, his obsessions and desires. He describes the collection as a dialogue, ‘between now and then, between the past of Alaïa, and its future’. Part of this was a bolder expression of sensuality from the designer; Mulier says that to him Alaïa is ‘beauty, body, sex – and it’s the only place where you can use the word sex without being vulgar. It’s sex that comes from the heart, from the inside, where beauty belongs and can be found.’

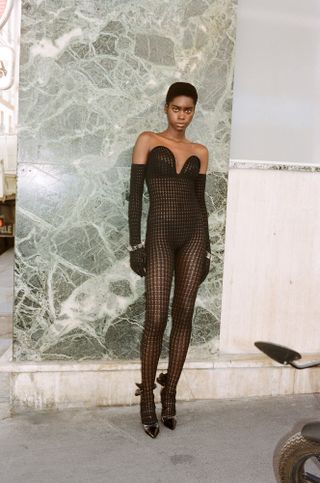

Catsuit, £1,940; gloves, £340; cuff, £490; shoes, £1,280, all by Alaïa

As such, the body is the core of the collection, with new proportions emphasised by the designer – he notes, in particular, a wider-cut shoulder exuding ‘confidence’ – while other garments have the illusion of floating on the body. Gowns, descending into ruffles, recall Alaïa’s 1980s Spanish dresses, here used for a play on volume, while a series of sheer-knit bodysuits sit flush to the body, demonstrating an impeccable mastery of shape and form. Tailoring – wide, oversized, worn resting on the shoulder – references a meeting between Alaïa and Greta Garbo, leading him to create a cocooning overcoat for the actress (‘big, bigger, biggest, with a collar to hide behind’, the notes described). A final artistic flourish comes in a collaboration with the Picasso Foundation, the abstract motifs on the artist’s ceramics adorning a series of dresses that rise up over the face like a mask. Mulier says these pieces provide a link between Alaïa, who was friends with the artist’s son Claude Picasso, Mulier himself, who designed the various pieces, and the ateliers, who were able to reimagine a great master’s work through craft and cloth.

‘Experimentation is essential, and can be done only with a strong connection to the ateliers. It’s what I learned when I started to work for Dior with Raf – thanks to them, you can bring a concept to life entirely by hand,’ he says. ‘These people are as creative as the creator, because you give an idea, you explain to them a little bit of what you want, or you make a sketch, and then all the rest is them putting their heart in it. This relationship between the creator and the hands of the ateliers is the soul of couture.’

Jack Moss is the Fashion Features Editor at Wallpaper*, joining the team in 2022. Having previously been the digital features editor at AnOther and digital editor at 10 and 10 Men magazines, he has also contributed to titles including i-D, Dazed, 10 Magazine, Mr Porter’s The Journal and more, while also featuring in Dazed: 32 Years Confused: The Covers, published by Rizzoli. He is particularly interested in the moments when fashion intersects with other creative disciplines – notably art and design – as well as championing a new generation of international talent and reporting from international fashion weeks. Across his career, he has interviewed the fashion industry’s leading figures, including Rick Owens, Pieter Mulier, Jonathan Anderson, Grace Wales Bonner, Christian Lacroix, Kate Moss and Manolo Blahnik.

- Spela Kasal - PhotographyPhotography

-

Bali welcomes Tri Hita Karana Tower, a hybrid sound and vision centrepiece

Bali welcomes Tri Hita Karana Tower, a hybrid sound and vision centrepieceTri Hita Karana Tower is launching at Bali's Nuanu City; designed by Arthur Mamou-Mani, it’s a new hybrid art-AI architectural landmark for the island

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Lego opens its first Superpower Studios at Paris’ La Gaîté Lyrique

Lego opens its first Superpower Studios at Paris’ La Gaîté LyriqueIn collaboration with Lego’s new Global Play Ambassadors, artists Aurélia Durand, Chen Fenwan and Ekow Nimako, and overseen by Colette co-founder Sarah Andelman, Paris is the site of the first Lego Superpower Studios

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

‘If kids grew up going to London Design Festival they would learn so much’: architect Shawn Adams

‘If kids grew up going to London Design Festival they would learn so much’: architect Shawn AdamsIn the first of our interviews with key figures lighting up the London Design Festival 2024, Shawn Adams, founder of POoR Collective, discusses the power of such events to encourage social change

By Ali Morris Published